The Physical Decline From Vascular Dementia:

A few years ago, my father-in-law started to complain about his balance, feelings of dizziness, and muscle weakness. Over a period of a few months he had fallen several times. One such fall led to a fractured right arm, serious enough to land him in hospital.

While there, a geriatrician diagnosed him with vascular dementia (VD), likely caused by several strokes (with one occurring in the basal ganglia, which are responsible for coordinating movement). The physician suspects my father-in-law now has a condition called festination, a slowness in movement characterized by shuffling of the feet. The progression of VD is described as a step-wise decline: the person functions in a steady state at one level and then declines to a new steady state (with this pattern repeating itself over time in a downward fashion).

Overall, the damage is robbing my father-in-law of his physical fitness; mainly affecting his lower body, especially his left leg. For him, the decline is rapid. It’s as if he’s receiving an execution-style shock, instantly rendering his body immobile. It takes days for the effect to wear off. But once complete, he begins to re-establish a new, albeit lower, steady state of function.

On bad days, he can barely move. On good days, he can walk at a turtle’s pace for about 20 to 30 feet (holding on to his wheelchair for balance), before he is out breath and his legs begin to shake. He looks as if he’s about to collapse from sheer exhaustion, like an elite marathoner crossing the finish line after running his personal best.

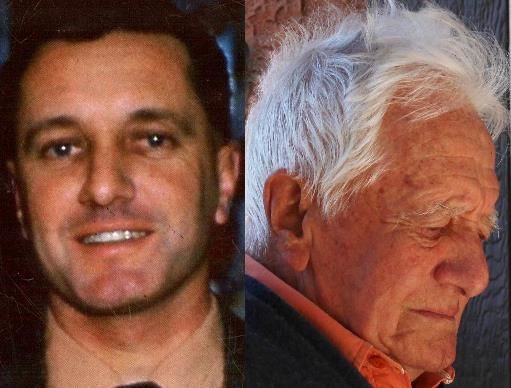

While I congratulate him for his effort, he laments; outwardly criticizing himself for not being able to walk further. He is grieving the man he used to be. It is so sad for him – and us to see this – as he was once a man who enjoyed a life full of physical activity.

Throughout his forty-year career as a civil engineer, my father-in-law was in charge of building nuclear and hydro-electric power plants in mountainous and forested country sides of Africa, Canada, India, Pakistan, and Malaysia (to name but a few places he worked – and lived). Mountain climbing in these places was one his favorite physical activities.

Whether it be tens of thousands of feet up Mt. Kilimanjaro in Tanzania to a few hundred feet through the foothills of the Canadian Rocky Mountains in Alberta, he climbed with competitive force. In his early sixties, he was able to reach the peak of Maxwell Hill in Malaysia (a 1,250 ft hike) faster than my husband and me (and we were in our mid-twenties).

Even in his retirement, he farmed a 250 acre plot of land in eastern Canada, growing apples and managing a large forested area of government planted trees. After he sold that and moved to Canada’s west coast, his love for the outdoors continued. He enjoyed going for walks along tree-covered pathways, or bike riding around town. Now, his physical condition has deteriorated to the point where he spends most of his time seated or lying down.

Climbing stairs is now as physically demanding as climbing the mountainous peaks he once enjoyed in his younger days. He grabs a hold of the banister with death grip force to avoid falling. He slowly pulls himself up, as if he his legs were weighted down with lead bricks. My husband calls it the Hillary Step: the last 40 feet of near vertical, ice-capped rock that Sir Edmund Hillary climbed to reach the summit of Mount Everest.

It is becoming increasingly more difficult for my father-in-law to navigate the steps on his own. We've now become his Sherpa, guiding him safely up to the top.

Our initial plan was for him to stay in our Calgary home until the end of the summer and then return to Vancouver, where my sister-in-law would again assume the caregiving role. We are now rethinking this plan because of the amount of assistance he requires. So, we had a family meeting to discuss his changing needs.

We have decided that he will remain in our house; at least until the winter sets in. We also discussed the likely need for home modifications, such as the installation of a wheelchair ramp, a stair lift, and perhaps an electric hoist to get him in and out of bed. I suggested we first get an occupational therapy (OT) assessment to help us determine his mobility needs based on his condition.

An OT can provide an overall plan with recommendations, including the best place to purchase or rent equipment. I will contact either the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (CAOT) or the Society of Alberta Occupational Therapists (SAOT).

We may have to pay for this service ourselves because my father-in-law likely won’t qualify for government funded services, nor does he have an extended health care plan to cover the cost. However, it may save us time and money in the future (i.e. get an assessment before we perhaps make unncessary changes to our home or buy equipment we may not need).

If you are experiencing age-related changes or are caring for an aging person who is, we’d love to hear your story at Disability Matters.

Comments (0)

This thread has been closed from taking new comments.

Related Posts

The Cognitive Decline From…

Family life can include the joy of getting a first job, marrying, and watching children grow. It can…

Read moreKeeping Safe on The Road…

In my last blog on motor vehicle accident (MVA) insurance, I focused on protecting your health. Today’s…

Read more