There Must Be A Reason Why

I am 10 years old. My brother and I, along with our parents, have just finished the tour of Hershey’s Chocolate factory in Hershey, PA. We are seated in their cafeteria and anxiously awaiting the mouth-watering taste of the chocolate treat my dad has just ordered.

In that moment, I have a glance encounter with a teenager who has Down syndrome. It is the catalyst of my intuition that one day I will have a child with a disability, and it roots itself into my consciousness, like a seed in soil.

As time goes on, I graduate high school and begin studying Kinesiology at university. I have no real careers plans in mind, but considering I love school and sports, it seems to be a good fit.

As a 19 year old, and in second year, I start taking electives in disability studies. Journal keeping is part of one elective: the future of mankind and his natural world. Alvin Toffler’s The Third Wave is required reading, and I’m instructed to use this to jar my futurist thinking on issues that matter to me.

One Journal entry:

September 28, 1983. THERE MUST BE A REASON WHY

I have this feeling, and have had it for many years that I will have a mentally handicapped child. People say that if you feel this way it does you more harm than good and that I should stop thinking these thoughts! Easier said than done.

Additional journal entries include thoughts on educating people with disabilities, wondering what life would be like being in a wheelchair, and the practicum I am taking working with adults with a disability.

The practicum is part of another elective course, Recreation 250: an introduction to leisure activities for special needs populations. It will mark one of the most pivotal learning experiences of my life.

My job is to to oversee three adults with a disability in a community swimming program: a woman with cerebral palsy (CP); a woman with a traumatic brain injury (TBI); and a man who has an overall developmental delay. I have no experience working with individuals with special needs. But, as a competitive swimmer, certified lifeguard, and swimming instructor, I know what to do in water – or so I think.

I meet them on the first night at the community centre. They are accompanied by their support worker. With the exception of him, we all change into our bathing suits and meet poolside. The three adults dawn life jackets. I help do them up.

There are two pools: the regular-sized, rectangular one; and a small, circular one, akin to a hot tub. By its size, I assume it’s for infant & parent swims. So, I am surprised the support worker instructs us to this, instead of the normal sized one.

Without question, I assist all three in and then climb in myself. The support worker remains at a distance.

The water is warm and only reaches our mid-waist. The man is rather large and so, takes up a good portion of the space.

“What kind of swimming are we going to do in here?” I think.

I continue to ponder its usefulness, when all of a sudden I look over to see the woman with the brain injury floating face down in the water. In this moment the pool couldn’t be small enough!

I quickly reach over, grab her around the shoulders, and lift her up. I wonder if my ‘rescue’ is too late. She is still breathing, but remains in an altered state of consciousness. I am at a loss of what to do next. So I just hold her.

Seconds later, she comes around, seemingly oblivious to her near death experience. By the end of our 30 minute swim, I will have rescued her several times over. I later learn that she suffers from petit mal seizures caused by the brain injury.

Several weeks go by at this practicum, with the only true life-guarding task of keeping the young woman with a brain injury alive! Surprisingly, I find myself enjoying the whole experience...up until the altercation I have with the man in my care.

While huddled together in that small pool one night, he forcibly grabs both my breasts. I am in shock. My brain turns off and my instincts take over: I wind up and give him a good slap across the face. No one, including the support worker, says or does a thing.

“Oh my God!” I think, as I lay my head in my hands. “I’ve just hit a defenseless, disabled person!” I have been socialized to believe people like this man don’t know what they are doing. So, the fact that I’ve hit him, means that I’m the one who is at fault.

My heart is beating fast. My mind is exploding with numerous and worried thoughts about my fate; the worst of which is me facing criminal charges for assault. At a minimum, I am certain I have failed the REC 250 course. But I have no more time to dwell on the matter, because I’m called upon, once again, to save the young women with the brain injury.

Finally, the swim ends. I hurriedly help get the women dressed and dress myself.

“I’ll quit the class and agree to receive a failing grade in exchange for no criminal charges being laid.” “I’ll do more community work, (with a promise never teach swimming to people with a disability).” “I’ll do anything, as long as I don’t get charged.”

I realize I’m pleading, in my mind’s eye, with the devil. I hastily exit the change room. I want to escape, if only to calm myself down. But the support worker stops me.

“Are you ok?”

“I’m fine,” I mutter. I’m really not, but I figure the less I say, the better it’ll be – after all, anything you say can and will be used against you in the court of law.

“It took a lot of guts to stand up to him,” he continues. “Most people in your situation would have done nothing.” He then tells me that my actions were as normal as expected, given what the man had done to me.

“To me?” I think.

The support worker continues: a main reason people with intellectual disabilities behave as badly as this man did to you, is because they rarely experience any real consequences for their inappropriate behaviour.

“Hmm,” I say. The light begins to dawn: he views me as the victim, not him. I exhale with a sigh.

“I think he’s learned his lesson,” the support worker concludes. “Oh, and by the way, you’re quite a natural with these adults.”

I’m not too sure what he means by this: I did hit the man. Nevertheless, a wave of relief washes over me as I discover that I’m not in any real trouble, nor have I jeopardized my practicum. Most importantly though, are the lessons that I learned that night:

- Poor behaviour requires natural consequences, regardless of one’s cognitive capacity;

- Natural consequences can only be realized by participating in normal activities – where else can we learn essential social skills such as getting along with others, turning taking, good manners, and the like.

A decade later, I begin my career as a rehabilitation case manager. I fit into this role like a key in a lock; primarily working with individuals who have sustained a traumatic brain injury or spinal cord injury from a car accident. For some, their injuries are so severe, they must relearn even the simplest of activities.

A key aspect of the rehabilitation plans I develop for them is participation in leisure or recreational activities. I only need to recall the lessons I learned in my REC 250 practicum to know that these kinds of activities are an important part of socializing.

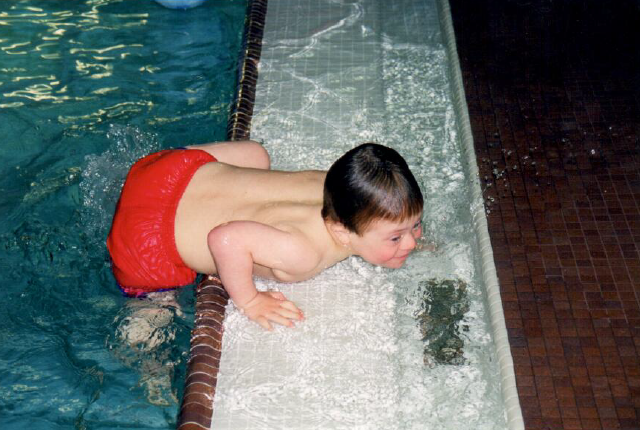

Shortly after I begin this career, my son with Down syndrome is born. That first intuition, seeded in my consciousness two decades earlier, has finally poked its head above the soil. He is the reason why. Needless to say, I don’t skip a beat in getting him swimming!

Share your life-changing event with us. We're hear to listen. Disability Matters!

Comments (0)

This thread has been closed from taking new comments.

Related Posts

Special Pups for Special…

In part one of my two-part blog, I introduced you to Brittany Harrison and her very special dog, Avery,…

Read moreSpecial Pups for Special…

Millennials are that group of young adults most often described as the “me” generation. Well, this…

Read more